This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

A Good Glass of Water

“Nevertheless, we love the city”, the revue singer Lulu Ziegler sang about Copenhagen in 1937. There had been good reasons for being hesitant a century earlier, too, at least when it came to the capital city’s supply of clean drinking water. It was nothing to write home about – unless one wanted to write a dirge.

It was bad, so bad in fact, that the Copenhageners, who have always had a flair for pithy word alterations, named the water that came out of their pumps, “The famous lukewarm eel soup”. And this was to be taken quite literally.

Rotten Fish

According to a contemporary account of the situation, the water could practically be used for a demonstration in natural history since mosquito larvae, leeches, salamanders and tadpoles all came out when Copenhageners pumped out water. Apparently, it was not a rarity neither that an eel as thick as a finger found its way through the pump, in which case the latter had to be taken apart. Rotten fish also occurred.

“Already in December 1849, passers-by on the street Købmagergade could see that something new was on the way”

Still, the representatives of the animal kingdom only constituted one part of the problems with the water, which, even with a filter apparatus and a water cooler, could not get below 14–17 degrees. When the old gutters in the neighbourhood around the street of Bredgade were taken up in 1844, a hole of more than ten centimetres was coincidentally discovered between the water conduit and the sewer line above, which among other things was receiving waste effluent from the morgue at Frederik’s Hospital. It has certainly not been particularly refreshing or hygienic. On the contrary, it helped foster the rampant epidemics of the period.

The Royal Spring

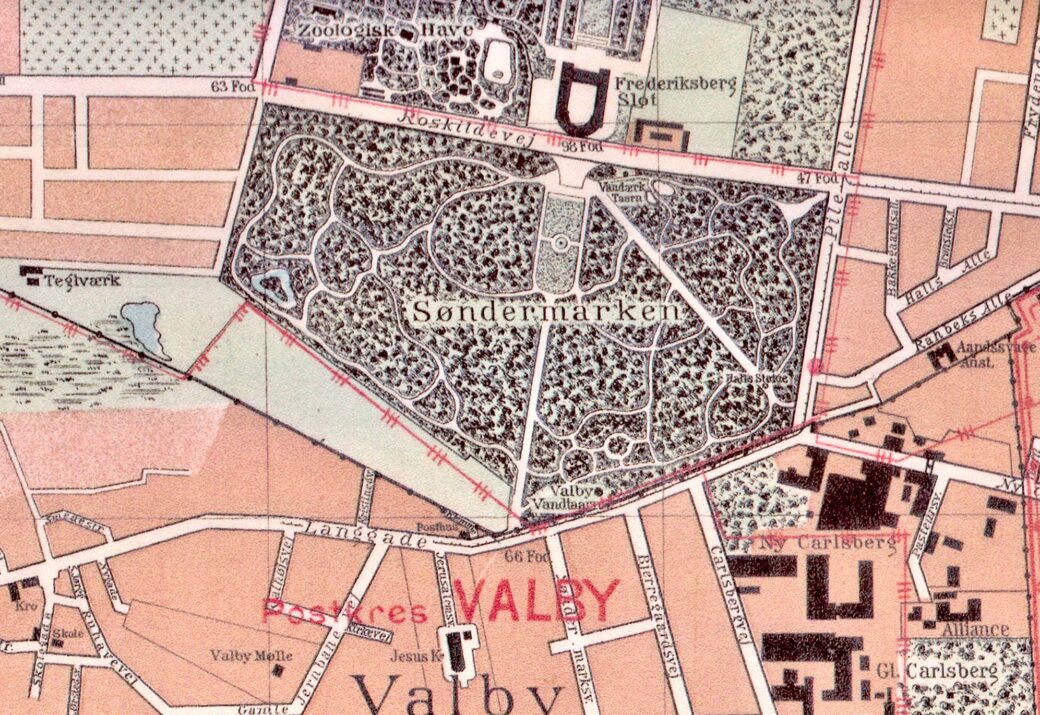

Although the water from the Copenhagen wells was a little more tolerable to drink than the water that was conveyed to the pumps through underground wooden conduits from lakes outside of the city, it is no wonder that inventive entrepreneurs in this period came up with the idea of importing drinking water to the Copenhageners from fresh, cool springs located in the hinterland of the city. Among these was the sacred spring Helligkors Kilde in Roskilde, which was already supplying the royal family with drinking water.

When Frederik IV fell ill in 1729 his doctors suggested him to get water from the spring, and when this seemingly proved to work as a cure, the water supply continued. In the 1730s the royal family thus collected 100 bottles at a time in Roskilde, and when Christian VI succeeded his father Frederik IV, he built a shed over the source of the spring, a bottling house next to it and a half-timbered house for the royal warden.

The conveyance of drinking water to the royal family lasted all the way to the 1840s, eventually taking place by train after the first railway opened in Denmark in 1847 between Roskilde and Copenhagen. Very much in the spirit of the decade of the Constitution, the supply of the exclusive drinking water was democratised when the master shoemaker, who had taken care of the conveyance of the royal water sought permission to expand the business so that the ordinary citizens of Copenhagen could also get “A good glass of water” as it was called in the original application from 1847 to the city government. That same year Olsen, which was what the master shoemaker was named, advertised with an invitation to subscribe to water from “the Royal Spring in Roskilde”. In the advertisement the water was described in the following way: “Due to its fineness and softness it is suitable as healthy and pleasant drinking water.”

A Small, Very Beautiful Temple

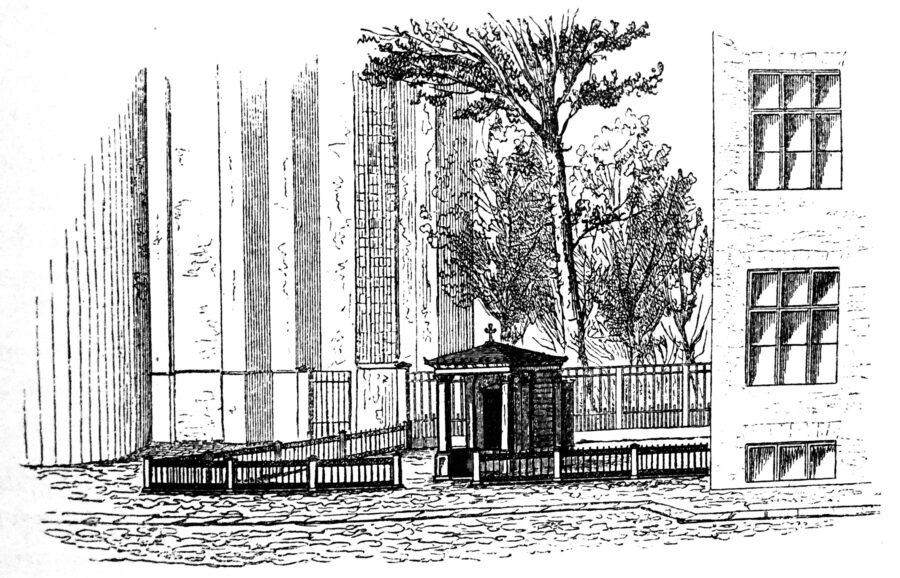

A few years later, the master shoemaker’s first serving stall was inaugurated. It was situated at the foot of the Round Tower – on the square between the tower and what is now the Student House (Studenterhuset). It was a meticulously furnished thing where in the water was stored under ground, so that it could be cooled with ice, before it was pumped up into another container from which it was bottled. And it was all well-thought-out. “For the buyer’s reassurance, each canister, where in the water is collected, comes with a signed note that shows the date of delivery”, the master shoemaker writes in an illustrated leaflet in which the project is recommended by the city’s public doctor, a professor and the Lord Chamberlain himself.

The water sale by the Round Tower opened in January 1850, but already in December 1849, passers-by on the street of Købmagergade could see that something new was on the way. “Next to the Round Tower a small, very beautiful temple is being build, it has a gold-plated cross on top and railing around it,” Hans Peter Jensen, a farmhand from Jutland who was in Copenhagen because of his military service, thus writes and continues: “Whilst it was being build, many were looking over the boards of the scaffold, curious to know what it was, but nobody knew. When it was finished and the boards were removed one could read on it: Water Container, for Drinking Water, from the Sacred Spring Hellig Kors Kilde by Roskilde. –”

Anniversary Water

Apparently, it was a very good business to sell water by the Round Tower, and according to some accounts the water sale even got an offshoot at the top of the tower. An article from 1913, which was published in the weekly magazine Illustreret Tidende, thus mentions a poster in the National Museum of Denmark that advertises for such an additional stall, but the poster is nowhere to be found in the museum and it was probably just a misunderstanding.

Even without a walk up the Spiral Ramp, the master shoemaker’s water stall on Købmagergade, which was gradually superseded by an actual waterworks in Copenhagen, is a good story. So good, that the Round Tower used it in its 350-year anniversary celebration on the 7 July 1987 and for this occasion once again got water from Roskilde that was sold out of a stall by the tower. This time, however, the water did not come from the sacred spring Helligkors Kilde, which had stopped to leap quite as freely in the meantime, but from another of the city’s many springs.